Visiting The Moche Ruins

Pyramids of the Moche

Pyramid building, art, ritual murder: all three flourished at the Moche huacas in northern Peru.

Archaeologists have long been spellbound by these pre-Columbian people, whose exquisite metalwork and vase painting frequently rival those of ancient Greece. Yet such beauty masks the darker aspects of Moche culture, among them a terrifying decapitator god and ceremonies drenched in human blood.

The Moche’s chief temples, the Huacas del Sol y de la Luna, were constructed between 0 and 500 AD, under the scabrous, ashy pile of Cerro Blanco near modern-day Trujillo.

Like the Aztecs, the Moche would continually add to their pyramids, building them upward and outward in ever-expanding layers. But suddenly, around 550 AD, this fierce desert people vanished, decamping for other sites to the north.

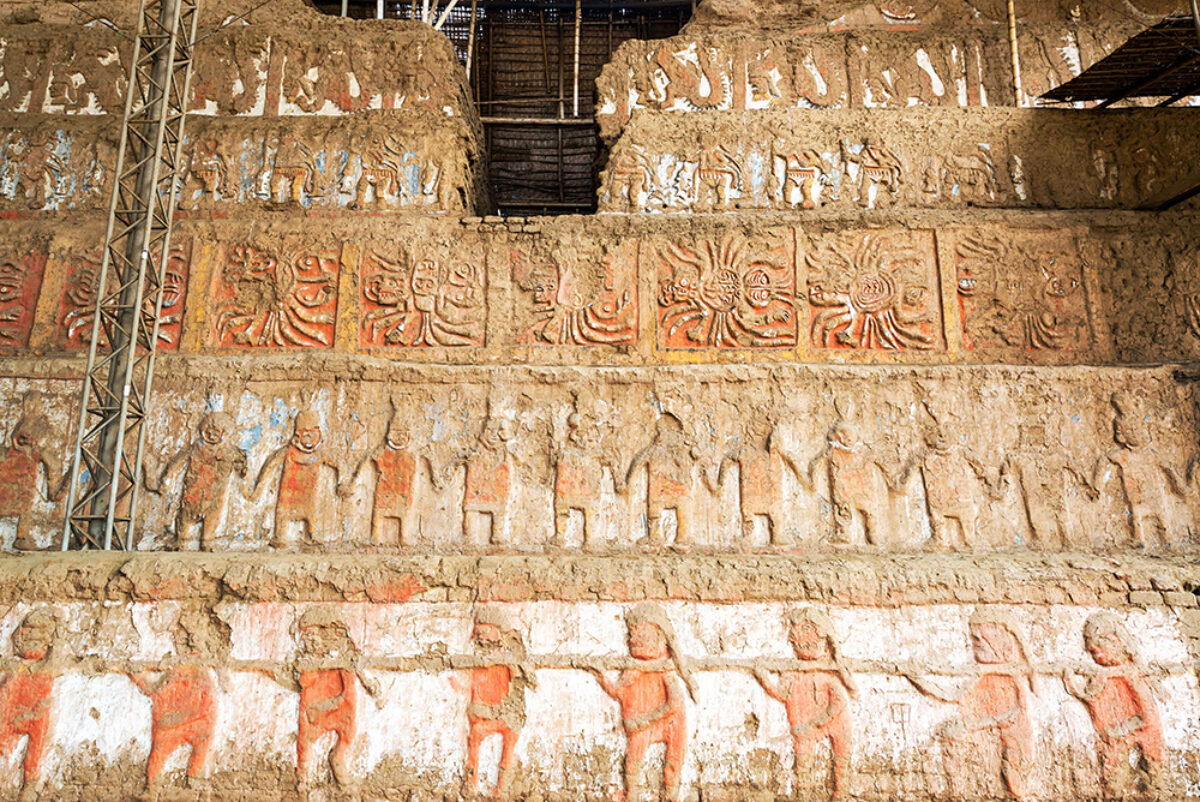

Friezes in the Moche Valley's Huaca de la Luna

How to visit the Moche ruins

Passing by the Huaca del Sol on the road to the Moche Valley, one’s first impulse is to mistake it for a huge hilly mound. Then, slowly, the eye picks out individual bricks from the sand, and the realisation dawns: this thing is man-made. Finally, the grey slopes of Cerro Blanco heave into view, and with them the crumbling walls of the Huaca de la Luna, shaded by protective awnings. This is the smaller but more interesting of the two pyramids.

It’s a scene of harshness, due to the site’s extreme decay. But it’s nothing compared to the strangeness inside.

The site

There are two structures remaining at what once was the Moche capital. The Huaca del Sol, or Temple of the Sun, is bigger, but paradoxically less impressive. Meanwhile, the smaller Huaca de la Luna, or Temple of the Moon, is for most visitors deathly fascinating.

The Huaca del Sol is situated on the western end below the city’s tutelary mountain. Time and human vandalism have done their worst, rendering it almost unrecognisable. At one point, it stood 160 feet high, with a summit platform in the shape of a cross and some 140 million bricks constituting its multiple layers. However, in 1602, the Spanish diverted the Moche River to wash out the gold from the tombs inside, destroying two-thirds of the pyramid in the process. Today, what was once the largest monumental structure in the Americas is a mere shell of its former self — and closed to the public too.

The Huaca de la Luna, meanwhile, is a labyrinth of surprises. Standing 105 feet tall, and composed of some 50 million adobe bricks, it was built at roughly the same time as the Huaca del Sol and is oriented around two main platforms (there are actually three, but the third is in a separate area, and not open for viewing). These two platforms are linked by a maze of plazas, ramps and terraces. The huaca was built over six successive centuries and generations, with each expanding on and completely covering the previous structure.

Platform two is the starting point for most tours. Here, in one of the grisliest rituals in all of pre-Hispanic America, the Moche would practice ritual human sacrifice, slitting the throats of tribal captives and stripping the flesh from their bones. Priests would then collect the victims’ blood in goblets and drink it before the assembled masses.

From that emotional high point, the tour advances to platform one, which is the roof of the huaca’s main structure. It’s divided into upper and lower areas, with the whole serving as another ceremonial area for priests. Here you can see some of the most impressive polychrome friezes left by the Moche — still vibrant in red, yellow, white, and black. Later, the tour winds through a sequence of galleries and plazas, before descending a 45-degree ramp to the main plaza below.

Key features

Some key features include:

Great Patio: On the lower level of the pyramid’s main platform, you’ll find murals of Ai-Apaec, the fierce creator god of the Moche religion. Depicted here with bulging eyes and sharp fangs, this octopus-like deity was known as the Decapitator for demanding the heads of his human victims.

Looter’s tunnel: From the corner of one of the plazas, it’s possible to look down into the tunnels carved by tomb-robbers in the 19th century. These openings were used to penetrate the pyramid and pillage its gold.

North façade: The north façade’s six-banded polychrome mural of religious and political subjects is impressive. Look for the chain gang of prisoners and the spiders depicting Ai-Apaec.

Rebellion of the objects: Moche mythology recounts the dark story of the “rebellion of the objects”, in which the technological implements created by humans rise up with murderous intent. See the mural near the pyramid’s north face.

The history of Moche Valley

The Huaca del Sol has received comparatively little scholarly attention. It may or may not have been a religious site, but the consensus is that it contained storage areas, tombs, and elite residences. The Huaca de la Luna, by contrast, appears to have been entirely sacred in nature; no domestic artifacts have ever been found there.

One of the latter huaca’s most fascinating aspects is its construction. At several points during the tour, gaps and tunnels open up that allow you to peer into the building’s bowels — and so witness the stages of its growth. The Moche, like the Aztecs, built up their pyramids in layers, adding a new outer shell over the old one every generation or so. Each time a priest died, he would be ceremonially buried inside the structure, and a new layer would be added for his successor to work in. In this way, the ecclesiastics would be transformed into ancestors, and the power of the priestly caste would be re-legitimated.

Moche culture

Moche civilisation began around the year zero, and gradually grew to encompass two different urban centres: one in the Moche Valley, the other further north near Pampa Grande. They were not an empire, but rather a loose confederation of city-states that shared culture and religion.

The Moche expanded considerably between 0 and 800 AD; at their peak, they held lands from Piura in the north to Huarmey in the south. Around 550, however, the gods abandoned the Moche: a horrific El Niño event brought torrential rains and then drought to Peru’s coast. They were forced to pack up and move north, first to Lambayeque, where they left the tombs at Sipán, and later to the surrounding desert, where they were lost to history.

Foremost among the Moche’s achievements is their art. Masters of every type of ceramic, they produced an astonishing array of pottery, from red-figure vases to stirrup vessels representing every variety of sex. For the interested, Lima’s Museo Rafael Larco Herrera has an entire room dedicated to Moche crockery depicting many different types of sexual practice.

The Moche were also highly skilled at metallurgy. Alloys, oxides, gilding and silvering, soldering, even electrochemical plating: almost every technique used by today’s artisans were known to Moche metal workers. This allowed them to make headdresses, chest plates, and beautiful tumi knives.

How to get to the Moche Valley

Half a day should be sufficient to see the pyramids. Signage at the Moche capital is minimal, but some of the local tour guides are excellent.

Included with admission to the site is a visit to the Museo Huacas de Moche, which includes highly informative displays about Moche art, history, religion and human sacrifice. Buses leave for the pyramids approximately every half an hour from Suarez in Trujillo or you can take a taxi.