Must-see Peru ruins

How to visit Peru's famous ruins and hidden gems

Peru is one of the most archaeologically-rich countries on earth, and not just because of its blockbuster site, Machu Picchu.

Indeed, the Inca of Machu Picchu fame were relative newcomers to pre-Columbian Peru; the final phase of a long series of human settlement that dates back to 9,000 BC – when civilisation in the so-called “old world” was just getting started.

Remnants of these ancient cultures are scattered across the country, many of which are easily accessible for casual visitors. And beyond the tourism honeypots around Cusco and the Sacred Valley, you’ll have many of these places more or less to yourself.

Here’s our run-down on some of the best – and lesser known – ruins and historical sites in Peru.

Choquequirao, not far from Machu Picchu and equally impressive, receives a fraction of the visitors

Visiting Peru's ruins

How to visit Peru's ancient ruins

Some of the following historical sites are known the world-over; others receive a trickle of visitors each year. All qualify as must-see sites on any visit to Peru.

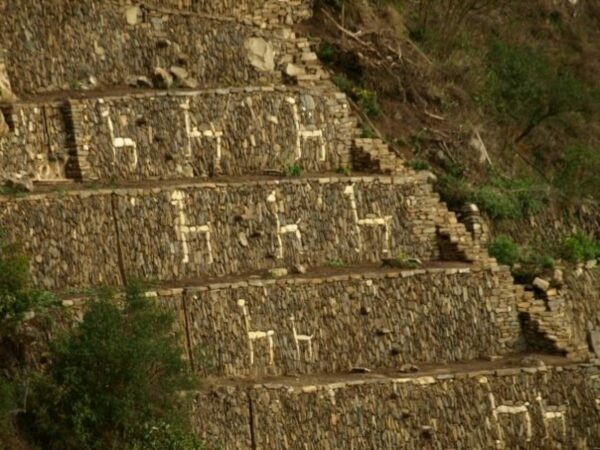

Choquequirao's uniquely decorated terraces

Choquequirao

Choquequirao was erected in the latter part of the 15th century, most likely under the reign of Tupac Inca Yupanqui (1471-1493). Like Machu Picchu, it was probably designed as a pleasure retreat and administrative centre for the Sapa Inca, but after the empire’s collapse in the late 1500s, it too lay abandoned and unknown for centuries.

As with its more famous sister, its obscurity owed a great deal to geography: the site lies on the far, unpopulated side of a peak overlooking the Apurímac River, at a height of some 10,000 feet.

Choquequirao is situated on a levelled hill saddle some 60 miles as the crow — or condor — flies from Cusco. Its location reflects the Inca notion of sacred geography: both the Apurímac River below and the glaciated 18,000-foot peak above were considered holy.

The site occupies seven square miles, three times the size of Machu Picchu, of which only 30% has been cleared of vegetation.

At least one full day is necessary to see Choquequirao properly. However, since visitors inevitably come equipped with camping gear, they can extend their time as long as they like. Two, three, even four-day stays are common to explore the many satellite precincts. The only limit is one’s eagerness to get back to civilisation.

Kuélap, the 'Machu Picchu of northern Peru'

Kuélap

Constructed by the Chachapoyas people, a formidable and mysterious pre-Inca civilisation who referred to themselves as ‘Warriors of the Cloud’, Kuélap was probably first settled sometime in the fifth or sixth century AD and gradually built up over almost a millennium. Current scholarly opinion posits it took on its present form sometime in the 1000s, remaining inhabited well into the 1500s. But as with all things Chachapoya, these dates are tentative at best.

For such a grand monument, Kuélap sees surprisingly few visitors. Those who do make the trek to the cloud forest are rewarded with some of the most spectacular pre-Columbian ruins in the continent.

Kuélap consists of some 16 acres of ruins atop a steep mountain ledge in what Peruvians call the ceja de la selva (eyebrow of the jungle) — the eastern side of the Andes that faces the Amazon. This means it’s surrounded by cloud forest, and on the many days in the region when it’s rainy, you’ll look down from the mountaintop on an abyss of fog.

Half a day is sufficient to tour the site. Monumental as the architecture is, only hardcore archaeology buffs will feel the need to spend more than four or five hours seeing it.

The afternoon sun shines on a quiet corner of Machu Picchu

Machu Picchu

No round-up of Peru's historical sites can ignore Machu Picchu and the Inca’s most famous archaeological site needs little introduction.

This mountaintop citadel has mesmerised foreigners the world over ever since a local family showed it to Hiram Bingham back in 1911. It’s a holy grail for travellers and scientists alike, where tourists can often watch archeologists at work and where new discoveries are still being made. Previously thought to have been built in the 1440s, in 2021 archeologists using radio-carbon dating showed it was inhabited as early as 1420. The discovery of new ceremonial water channels was published as recently as 2022.

Classic Inca terraces overlooking the Sacred Valley at Ollantaytambo

Ollantaytambo

Ollantaytambo presides over the western end of the Sacred Valley, the counterpart to Pisac and a site of almost incomprehensible architectural engineering.

Spanish chroniclers dubbed it a fortress, and it was the site of a major battle between the Spanish and the Inca in January 1537 when the Spanish suffered their only major defeat at the hands of ruler Manco Inca. Perhaps this is why the Spanish never reached Machu Picchu, as Ollantaytambo guards the valley that leads to that most famous of Inca sites.

Today, Ollantaytambo is considerably more peaceful, but just as imposing. After climbing the 200-plus stairs to the top, visitors will find a sun temple, an enclosure of ten niches, and the unfinished moon temple. At the foot of the impressive structure is a series of gardens with a lovely ceremonial bath carved from a single block of stone. Best of all, the archeological site is next to the cobbled streets of the eponymously named village — the most complete Inca town that’s still inhabited.

Intriguing circular terraces of Moray

Moray

The name Moray comes from the Quechua word amoray, which means corn harvest. The name is apt, for these stunning, 500-foot-deep circular terraces were likely some of the hemisphere’s first laboratories for agricultural science. Green technology more than 500 years before today, they’d have been invaluable to the Inca’s control of the food supply for much of South America.

Modern investigators have observed a 1 degree Celsius differential from one terrace to the next, warming the deeper you go into the basins. This would have allowed Inca scientists to simulate different microclimates in the Andes as they tested out new seeds and crop species.

Remains of the water temple at Tambomachay

Credit: Heather JasperQ’enqo, Puka Pukará & Tambomachay

These three sites are almost always visited together and are sold by tour operators as the Cusco “city tour.” They are not actually in the city of Cusco but are in the hills above Sacsayhuamán. All three are small and an hour each is sufficient.

It is easier to visit on a tour, which will also include a guide, though you may feel rushed in a group tour. If you are new to the high altitude, you can take a bus tour of these sites. From the top of the double-decker “mirabus” you can see Sacsayhuamán, Q’enqo and Puka Pukará without any walking.

Chavín de Huántar: "The birthplace of South American culture"

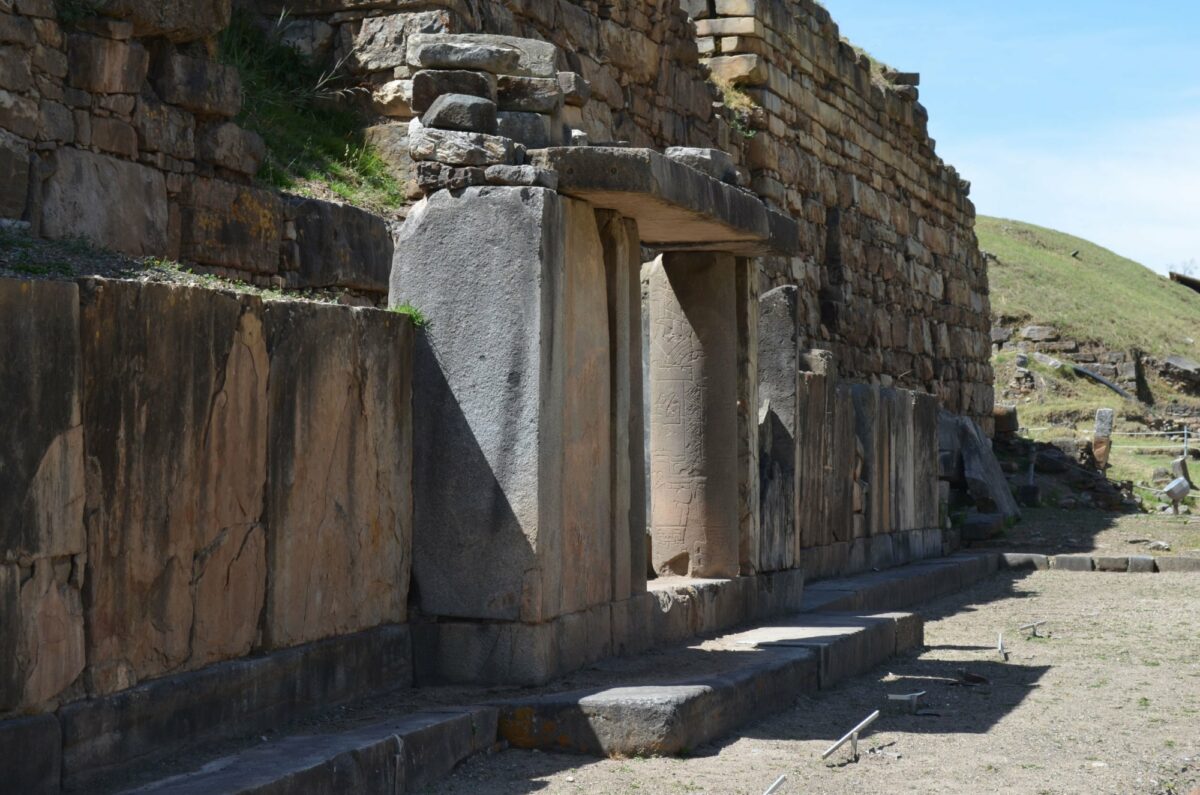

Chavín de Huántar

“The birthplace of South American culture” — such was the great Peruvian archaeologist Julio C. Tello’s epithet for Chavín de Huántar. Time may have qualified his judgment, but it’s done nothing to alter its basic rightness.

Chavín de Huántar was built by the Chavín people, a prehistoric Andean culture that takes its name from the site and that flourished between 900 and 200 BC. Most archaeologists believe the site was constructed in two stages: the so-called Old Temple took shape from 1,000 to 500 BC, while the adjoining New Temple was added between 500 and 200 BC. The resultant complex was in its day the most important pilgrimage destination in the Andes: worshippers would travel thousands of miles to participate in its sacred rituals and consult its oracle. Meanwhile, Chavín textiles, metalwork, and ceramics served to spread the monotheistic cult of a bizarre fanged deity throughout Peru.

The Chavín ruins are not especially impressive at first glance. Yet as one gets closer, one senses the place’s uncanny spiritual presence. The first sight upon arrival is a vast sunken courtyard, grass-covered and flanked by platforms. Next comes the grey-brown sandstone face of the New Temple, with its columned portal and protective scaffolding. Finally, continuing to the right, one arrives at the Old Temple, with another sunken courtyard. Not much to look at — but the true payoff is inside.

Half a day should suffice to see the ruins; many visitors take day trips from Huaraz in the Cordillera Blanca. If you want to see the complex early in the morning and explore the site’s museum at your leisure, overnight stays at the mountain town of Chavín are highly recommended.

Sacsayhuamán, overlooking the city of Cusco

Sacsayhuamán

Stones weighing over 300 tonnes; stacked tiers of zig-zagging walls; high towers overlooking the Inca capital from a soaring hilltop: everything about Sacsayhuamán is truly gargantuan — and this despite the fact that only 20% of this stunning temple remains intact.

Sacsayhuamán was built in the 15th century on a high hill overlooking Cusco from the west. The massive walls understandably confused Spanish historians, who classified the site as a fortress. Adding to the confusion, it was the site of a battle in 1536 between the Spaniards and the Inca that was one of the turning points of the conquest.

Pachacamac, on the outskirts of Lima, the Peruvian capital

Pachacamac

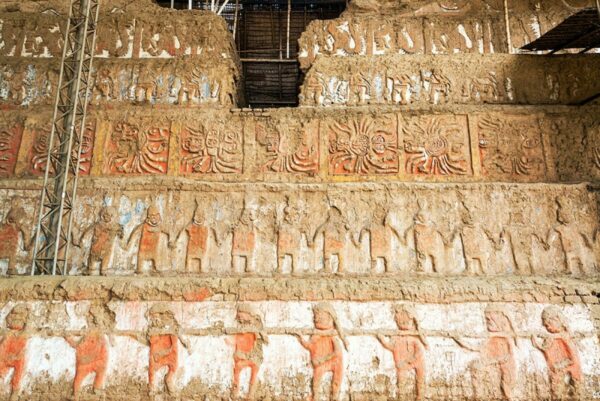

Pachacamac was, for 1,500 years, the most important temple on the Pacific seaboard of South America. First inhabited by the Lima culture around 300 AD, it was later expanded by the Huari, a highland tribe who turned it into a major pilgrimage destination circa 700. Last came the Inca, who ruled it from the 1400s until the site’s dismantling by the Spanish in 1532.

What made the sanctuary such a hot property? Principally, its oracle of Pachacamac — ‘he who shakes the earth’. Feared as the creator god responsible for earthquakes, this strange, fish-faced deity was represented on an ornately carved wooden staff that local rulers would consult to divine the future.

Later, votaries would pass through the complex’s criss-crossing alleys and offer sacrifices atop its platforms, which include the red-and-yellow-frescoed Painted Temple and the Temple of the Sun. All of these crumbling ruins are still visible today, along with a reconstructed sanctuary for aqlla, holy virgins who were not allowed any contact with men unless the Inca took them as a wife.

Pachacamac is located some 25 miles from downtown Lima on the Panamericana highway. Signage is minimal, but there’s an excellent new on-site museum, and guides are available. Take plenty of water and sunscreen when you go: the track through the complex is long and dusty. It's not the most overwhelming of sites, but its proximity to Lima makes it a convenient day trip from the city.

Huaca Pucllana which, in central Lima, doesn't get much more convenient

Huaca Pucllana

For out-of-towners, it might seem bizarre to find a pre-Columbian pyramid in the heart of Miraflores, Lima’s ultra-modern tourist district. For limeños, however, sites like Huaca Pucllana are just part of the scenery -- everyday fare in a capital that dates back 2,000 years.

Huaca Pucllana was built around 400 or 500 AD by the Lima, a pre-Hispanic civilisation that occupied the central Peruvian coast. Originally a ceremonial site where shark-eating and pottery-smashing were frequent rituals, it was overrun sometime around 700 by the Huari, a militant highland tribe who converted it into a huge necropolis. Today, tour guides take you up to the temple ramparts, where you’ll see the tombs of elite Huari women sacrificed to the gods, along with their children. There’s also a small zoo with llamas and alpacas, and an informative museum.

Huaca Pucllana is a good option for families with kids: an on-site programme allows youngsters to dig for small artefacts. Meanwhile, adults will enjoy the spectacular nighttime views of the pyramid from the terrace of the adjoining restaurant, which is one of the best in Lima.

Eerie tombs of Sipán

Sipán

In 1987, Peruvian archaeologist Walter Alva had an Indiana Jones moment. Called by Peru’s police to investigate some stolen pre-Hispanic artefacts in the northern city of Chiclayo, he was rushed out to Huaca Rajada, an earth-covered pyramid outside of town, where he encountered a group of tomb raiders pillaging a Moche burial site. Alva succeeded in stopping the looters, but in the process, he stumbled on one of the great archaeological finds of the 20th century.

The find was El Señor de Sipán, a Moche lord who ruled around 200 AD and was interred in an ornate tomb with his eight-person entourage (a Moche high priest was buried nearby). That in itself would have been major news, but the hoard of gold, turquoise, and ceramic objects that came with it made it the richest burial site ever found in the Western hemisphere. Today, visitors can stand beneath Huaca Rajada and see mock-ups of the original excavations, but the real glories of Sipán are indoors, in its two fascinating museums.

Most of the artifacts from Alva’s discovery are now in the Museo Tumbas Reales de Sipán in Lambayeque, a world-class showcase for the pectoral plates, earrings, nose shields and sceptres unearthed with the Moche lord. The museum is well organised, with informative displays and guides throughout. Also worth a visit is the Museo de Sitio Sipán, located right at Huaca Rajada and filled with some of the overflow from the Museo Tumbas Reales. A rare instance in Peru in which the museum exhibits are more interesting than the archaeological site itself.